Developing a Policy on the

Use of Social Media

in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Guidance and Recommendations

Global Justice

Information

Sharing

Initiative

February 2013

Developing a Policy on the

Use of Social Media

in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Guidance and Recommendations

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................................1

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................5

Social Media Policy Elements .......................................................................................................... 11

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 19

Appendix A—Cases and Authorities ............................................................................................ 21

Appendix B—Georgia Bureau of Investigation Social Media Policy ................................. 29

Appendix C—Dunwoody Police Department Social Media Policy ................................... 37

Appendix D—New York City Police Department Social Media Policy ............................. 41

This project was supported by Grant No. 2010-MU-BX-K019 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs,

U.S. Department of Justice, in collaboration with the Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative. The opinions, findings, and

conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

U.S. Department of Justice.

iv Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Executive Summary

The advent of social media sites has created an environment of

greater connection among people, businesses, and organizations,

serving as a useful tool to keep in touch and interact with one

another. These sites enable increased information sharing at a

more rapid pace, building and enhancing relationships and helping

friends, coworkers, and families to stay connected. Persons or groups

can instantaneously share photos or videos, coordinate events,

and/or provide updates that are of interest to their friends, family,

or customer base. Social media sites can also serve as a platform

to enable persons and groups to express their First Amendment

rights, including their political ideals, religious beliefs, or views on

government and government agencies. Many government entities,

including law enforcement agencies, are also using social media sites

as a tool to interact with the public, such as posting information on

crime trends, updating citizens on community events, or providing

tips on keeping citizens safe.

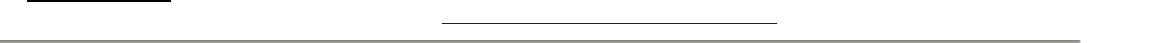

Social media sites have become useful tools for the public and law enforcement entities, but criminals are also using these

sites for wrongful purposes. Social media sites may be used to coordinate a criminal-related ash mob or plan a robbery,

or terrorist groups may use social media sites to recruit new members and espouse their criminal intentions. Social

media sites are increasingly being used to instigate or conduct criminal activity, and law enforcement personnel should

understand the concept and function of these sites, as well as know how social media tools and resources can be used to

prevent, mitigate, respond to, and investigate criminal activity. To ensure that information obtained from social media sites

for investigative and criminal intelligence-related activity is used lawfully while also ensuring that individuals’ and groups’

privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties are protected, law enforcement agencies should have a social media policy (or include

the use of social media sites in other information-related policies). This social media policy should communicate how

information from social media sites can be utilized by law enforcement, as well as the diering levels of engagement—such

as apparent/overt, discrete, or covert—with subjects when law enforcement personnel access social media sites, in addition

Social media sites are increasingly

being used to instigate or

conduct criminal activity, and law

enforcement personnel should

understand the concept and function

of these sites, as well as know how

social media tools and resources can

be used to prevent, mitigate, respond

to, and investigate criminal activity.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 1

to specifying the authorization requirements, if any, associated with each level of engagement. These levels of engagement

may range from law enforcement personnel “viewing” information that is publicly available on social media sites to the

creation of an undercover prole to directly interact with an identied criminal subject online. Articulating the agency’s

levels of engagement and authorization requirements is critical to agency personnel’s understanding of how information

from social media sites can be used by law enforcement and is a key aspect of a social media policy.

Social media sites and resources should be viewed as another tool in the law enforcement investigative toolbox and should

be used in a manner that adheres to the same principles that govern all law enforcement activity, such as actions must

be lawful and personnel must have a dened objective and a valid law enforcement purpose for gathering, maintaining,

or sharing personally identiable information (PII). In addition, any law enforcement action involving undercover activity

(including developing an undercover prole on a social media site) should address supervisory approval, required

documentation of activity, periodic reviews of activity, and the audit of undercover processes and behavior. Law

enforcement agencies should also not collect or maintain the political, religious, or social views, associations, or activities

of any individual or group, association, corporation, business, partnership, or organization unless there is a legitimate

public safety purpose. These aforementioned principles help

dene and place limitations on law enforcement actions and

ensure that individuals’ and groups’ privacy, civil rights, and

civil liberties are diligently protected. When law enforcement

personnel adhere to these principles, they are ensuring that

their actions are performed with the highest respect for the

1. Articulate that the use of social media resources will be consistent with applicable laws, regulations, and

other agency policies.

2. Dene if and when the use of social media sites or tools is authorized (as well as use of information on

these sites pursuant to the agency’s legal authorities and mission requirements).

3. Articulate and dene the authorization levels needed to use information from social media sites.

4. Specify that information obtained from social media resources will undergo evaluation to determine

condence levels (source reliability and content validity).

5. Specify the documentation, storage, and retention requirements related to information obtained from

social media resources.

6. Identify the reasons and purpose, if any, for o-duty personnel to use social media information in

connection with their law enforcement responsibilities, as well as how and when personal equipment may

be utilized for an authorized law enforcement purpose.

7. Identify dissemination procedures for criminal intelligence and investigative products that contain

information obtained from social media sites, including appropriate limitations on the dissemination of

personally identiable information.

A Social Media Policy Should

Address These Key Elements

2 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

law and the community they serve, consequently fostering the community’s trust in and support for law enforcement

action.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA)—with the support of the Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative (Global)

Advisory Committee (GAC), a Federal Advisory Committee (FAC) to the U.S. Attorney General on justice-related information

sharing, and the Criminal Intelligence Coordinating Council (CICC)—has developed the resource Developing a Policy on

the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities: Guidance and Recommendations, which provides law

enforcement leadership and policymakers with recommendations and issues to consider when developing policy related to

the use of social media information for criminal intelligence and investigative activities. A social media-related policy (or a

policy that includes procedures on the use of social media information) will help protect the law enforcement agency and

agency personnel and will also help ensure the continued protection of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties of individuals

and groups in the community.

The Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities: Guidance and Recommendations

is designed to guide law enforcement agency personnel through the development of a social media policy by identifying

elements that should be considered when drafting a policy, as well as issues to consider when developing a policy, focusing

on privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties protections. This resource can also be used to modify and enhance existing policies

to include social media information. All law enforcement agencies, regardless of size and jurisdiction, can benet from the

guidance identied in this resource.

The key elements identied in this resource can be applied to “traditional” social media sites (such as Facebook, Twitter,

and YouTube) and are also applicable as dierent and new types of social media sites emerge and proliferate. As a policy is

developed, the agency privacy ocer and/or legal counsel should be consulted and involved in the process. Additionally,

many agencies have an existing privacy policy that includes details on how to safeguard privacy, civil rights, and civil

liberties, and an agency’s social media-related policy should also communicate how these protections will be upheld when

using information obtained from social media sites.

Social media sites have emerged as a method for instantaneous connection among people and groups; information

obtained from these sites can also be a valuable resource for law enforcement in the prevention, identication,

investigation, and prosecution of crimes. To that end, law enforcement leadership should ensure that their agency has

a social media policy that outlines the associated procedures regarding the use of social media-related information in

investigative and criminal intelligence activities, while articulating the importance of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties

protections. Moreover, the same procedures and prohibitions placed on law enforcement ocers when patrolling the

community or conducting an investigation should be in place when agency personnel are accessing, viewing, collecting,

using, storing, retaining, and disseminating information obtained from social media sites. As these sites increase in

popularity and usefulness, a social media policy is vital to ensuring that information from social media used in criminal

intelligence and investigative activities is lawfully used, while also ensuring that individuals’ and groups’ privacy, civil rights,

and civil liberties are diligently protected.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 3

4 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Introduction

In recent years, social media sites

1

have emerged as a useful tool for

friends, coworkers, and families to keep in touch and interact with one

another. Persons and groups can share photos or videos, coordinate

meet-ups or plans for the weekend, and/or provide updates on

newsworthy events to their friends, family, or customer base. One of

the goals of these types of sites is instantaneous connections among

people, businesses, and organizations, leading to greater and quicker

sharing of information and enhanced relationships. Social media sites

can also serve as a platform to enable people to express their First

Amendment rights, including their political ideals, religious beliefs,

or disappointments with government agencies. Many government

entities, including law enforcement agencies, are now using social media

sites to interact with the public and provide information on crime trends

and community events and tips for keeping citizens safe.

In addition to these types of information sharing exchanges between

and among persons and entities, social media sites have become a

tool that criminals are using for nefarious and criminal purposes. Examples of the use of social media to conduct criminal

activity include individuals coordinating a criminal-related ash mob

2

or utilizing a social media site to plan a robbery,

online predators joining a social media site to identify and interact with potential victims, and terrorist groups using social

media to recruit new members and espouse criminal intentions. Because social media sites are increasingly being used to

instigate and conduct criminal activity, law enforcement personnel should understand the concept and function of social

media sites and know how social media tools and resources can be used to prevent, mitigate, respond to, and investigate

criminal activity.

1 The International Association of Chiefs of Police’s (IACP) Center for Social Media denes social media as “a category of Internet-based

resources that integrate user-generated content and user participation. This includes, but is not limited to, social networking sites (Facebook,

MySpace), microblogging sites (Twitter), photo- and video-sharing sites (Flickr, YouTube), wikis (Wikipedia), blogs, and news sites (Digg, Reddit).”

2 A ash mob is a “group of people, usually organized through social media or text message, that gather at a location to perform a

specic action before dispersing. These actions may be for entertainment or criminal purposes.” (http://www.IACPsocialmedia.org/glossary)

To successfully and lawfully harness the

power and value of social media sites,

while ensuring that individuals’ and

groups’ privacy, civil rights, and civil

liberties are protected, agency leadership

should support the development of a

policy within their agency regarding

the use of social media sites in criminal

intelligence and investigative activity.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 5

Social media sites can be valuable sources of information for

law enforcement personnel as they fulll their public safety

mission—agency public information ocers may use social

media to interact with the public, detectives may access social

media sites to assist in the identication and apprehension of

criminal subjects, intelligence analysts may utilize social media

resources as they develop intelligence products regarding

emerging criminal activity, and fusion center analysts may use

social media resources to assist in the development of analytic

assessments. To successfully and lawfully harness the power

and value of social media sites, while ensuring that individuals’

and groups’ privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties are protected,

agency leadership should support the development of a policy

within their agency regarding the use of social media sites in criminal intelligence and investigative activity.

3

To assist agencies in drafting a social media policy, the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA)—with the support of the Global

Justice Information Sharing Initiative (Global) Advisory Committee (GAC), a Federal Advisory Committee (FAC) to the U.S.

Attorney General on justice-related information sharing, and the Criminal Intelligence Coordinating Council (CICC)—has

developed this resource to provide law enforcement leadership and policymakers with recommendations and issues

to consider related to the use of information obtained from social media sites as a part of criminal intelligence and

investigative activities.

4

It is recommended that all law enforcement leadership support the development of a social media-related policy and

associated procedures (or enhance existing policies) to guide personnel on accessing, viewing, collecting, storing,

retaining, and disseminating (or using) information from social media sites, tools, and resources as a part of their authorized

investigative and criminal intelligence activities.

5

A written policy assists in the protection of the agency and agency

personnel, as well as the individuals and groups in the community. With the advent of the Internet and, specically, social

media sites, the expectation of privacy has changed. Individuals and groups regularly make openly available various

pieces of information of themselves (e.g., photos, relationship links, current locations, dates of birth); while in many

cases this information is public and available to anyone with Internet access, law enforcement personnel should use this

type of information only based upon a valid law enforcement purpose (i.e., consistent with legal authorities and mission

requirements). A policy will assist agency personnel in identifying and understanding their purpose and limitations

regarding the use of information from social media sites, the need to document this purpose, and the importance of

protecting the public from inadvertent or intentional misuse of information obtained from social media sites.

This resource is designed to identify elements that should be considered for inclusion in a social media policy, issues to

consider when developing a policy, and examples of the use of social media as an investigative or intelligence-related tool,

focusing on the protection of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties of individuals and groups. The tenets identied in this

resource can be used to draft a new policy or enhance existing information and criminal intelligence-related policies.

3 Agency leadership may also incorporate the tenets identied in the paper into existing policies and procedures (such as policies on

criminal intelligence and/or criminal investigations).

4 For purposes of this resource, law enforcement may be broadly dened to include all activities related to crime prevention or reduction

and the enforcement of the criminal law. However, it is important to note that certain law enforcement or criminal justice agencies may be

subject to additional constraints regarding access, use, or disclosure of social media sites and information. For example, prosecutors’ oces must

adhere to constitutional and statutory discovery and ethical standards that would not apply to police agencies. Consequently, nonpolice law

enforcement agencies (such as state attorneys’ oces or other prosecutorial entities) will need to take any unique considerations into account in

developing a social media policy.

5 For the purpose of this document, accessing, viewing, collecting, storing, retaining, and disseminating information obtained from

social media sites, tools, and resources will be referred to as using information obtained from social media sites, tools, and resources.

6 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Audience

All law enforcement agencies, regardless of size—from a small,

rural agency to a large, metropolitan law enforcement agency

to a state or urban area fusion center—can benet from the

recommendations identied in this document. As agency

policymakers review the components of this resource, it should

be understood that social media is, in essence, simply another

resource for law enforcement personnel to use in the performance

of their public safety mission. The same basic policing principles

apply in the use of social media as with other law enforcement

action.

6

It is important to provide all agency personnel—from

leadership to analysts to detectives and investigators to uniformed

patrol ocers—with pertinent and applicable guidance to

ensure that social media resources are being utilized in a lawful and appropriate manner, a manner that upholds the

agency’s mission and legal authorities and complies with applicable federal, state, and tribal laws and local ordinances. As

agencies develop and adapt a policy on using social media information as a part of their investigative and intelligence-

related activities (or enhance existing policies), it is recommended that the agency privacy ocer and/or legal counsel be

consulted and be involved in the development and implementation process.

The Protection of Privacy, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties

As with all law enforcement activity and actions, individuals’

privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties must be diligently

protected, and the proliferation of social media sites and

technology has led to a renewed focus on these protections.

Social media resources not only provide a new forum

and format for free speech but also introduce a potential

risk to individuals’ privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties if

unauthorized or inappropriate access or use occurs. To

mitigate such risks, law enforcement ocers and agency

personnel are trained to ensure the protection of these rights

while performing their duties, be it providing security at a

public rally, conducting a criminal investigation, or developing

criminal intelligence.

7

This type of training may also be applicable to the use of social media sites in investigative and

intelligence activities and the privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties implications associated with access to social media sites

and the use of information obtained from such sites.

In addition to training, many agencies have a privacy policy that includes details on how to protect individuals’ and groups’

privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties.

8

To support and enhance the agency’s privacy policy, agencies should also have a

policy regarding social media (or enhance existing information and criminal intelligence-related policies) that articulates

how these protections will be upheld when using information obtained from social media sites and resources.

6 See the section titled “Law Enforcement Principles” for additional information on these principles.

7 An example of privacy training for line ocers is available at http://www.ncirc.gov/training_privacylineocer.cfm.

8 Additional information on how to develop a privacy policy is available at http://www.it.ojp.gov/privacy.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 7

Uses of Social Media

Social media may be used by law enforcement

personnel in their daily functions in a number of areas,

including:

• Pre-employment background investigations

• Outreach and community engagement

• Emergency alerts and notications

• Analytic assessments

• Situational awareness reports

• Intelligence development

• Criminal investigations

Additional guidance for law enforcement agencies and personnel regarding pre-employment background investigations,

outreach and community engagement, and emergency alerts and notications is accessible via the International

Association of Chiefs of Police’s (IACP) Center for Social Media Web site, http://www.IACPsocialmedia.org/.

Analytic assessments and situational awareness reports can be designed to provide information to law enforcement on a

specic topic to assist agencies in maintaining public safety. These assessments may serve as a gauge for determining the

types of criminal activity within a region or determining whether there are threats related to an upcoming public event.

9

Information from social media sites may be referenced in an analytic assessment that identies current levels of criminal

activity within an agency’s jurisdiction. For example, an agency may search Twitter feeds, which may contain information

on gang-related activities, and Flickr, which may include pictures of gang-related grati. This information may then be

referenced in an assessment to provide examples of the types of gang activity occurring within a certain area.

As it relates to criminal intelligence development and criminal investigations, information from social media sites may be

used as a part of criminal-related background investigative activities. For example, a criminal subject’s Facebook page may

be accessed to further support the identication of the subject and/or acquaintances. Social media sites and resources

may also be used to determine a timeline of events for a suspect. For example, when a person “checks in” on the Web site

FourSquare at a certain date and time, this information may be accessible by Facebook users. The individual may then post

a picture of himself at this location, which may also be geotagged

10

via a smartphone and uploaded by the individual to

Twitter.

There are an ever-increasing number and variety of social media sites: simple Web sites to post short pieces of information,

virtual worlds (e.g., Club Penguin, Second Life, massively multiplayer online role-playing games, or online gambling sites),

photo-sharing sites, and online forums and comment areas. Although this document will focus on “traditional” social media

sites while acknowledging the continuing emergence and proliferation of dierent types of social media, it should be

understood that the elements set forth in this paper may be applied to all types of social media sites and resources.

9 Additional information on responding to First Amendment-protected events is found in the Recommendations for First Amendment-

Protected Events for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, available at http://it.ojp.gov/documents/First_Amendment_Guidance.pdf.

10 The terms geolocation/geotagging, dened at www.IACPsocialmedia.org/glossary, refer to the incorporation of location data in various

media, such as, for instance, a photograph, a video, or an SMS message. This may be used on social media platforms to notify people where a user

is at a given time.

8 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Elements of a Social Media Policy

The purpose of a social media policy is to dene and

articulate acceptable law enforcement practices related

to using information obtained from social media sites.

As a part of a social media policy, agency leadership

should reference other related policies and/or general

orders regarding both criminal intelligence and criminal

investigations, including an agency’s privacy policy or

policy regarding undercover activities. Because social

media sites can be used to support these functions, it is

important to ensure consistency and continuity between

policies or orders.

Key elements of a social media policy include:

1. Articulate that the use of social media resources will be consistent with applicable laws, regulations,

and other agency policies.

2. Dene if and when the use of social media sites or tools is authorized (as well as use of information

on these sites pursuant to the agency’s legal authorities and mission requirements).

3. Articulate and dene the authorization levels needed to use information from social media sites.

4. Specify that information obtained from social media resources will undergo evaluation to determine

condence levels (source reliability and content validity).

5. Specify the documentation, storage, and retention requirements related to information obtained

from social media resources.

6. Identify the reasons and purpose, if any, for o-duty personnel to use social media information in connection

with their law enforcement responsibilities, as well as how and when personal equipment may be utilized for

an authorized law enforcement purpose.

7. Identify dissemination procedures for criminal intelligence and investigative products that contain

information obtained from social media sites, including appropriate limitations on the dissemination

of personally identiable information (PII).

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 9

Law Enforcement Principles

Interwoven within these policy elements is the

acknowledgement that social media sites and resources

are another tool in law enforcement’s toolbox of

information sources. As such, social media sites and

resources should be utilized in a manner that adheres

to the same principles that govern all law enforcement

actions. These principles include:

• Law enforcement actions must be lawful.

• Law enforcement actions should conrm with

community standards, when appropriate.

• Law enforcement actions must have a dened

objective and a valid law enforcement purpose

for gathering, maintaining, or sharing personally

identiable information about criminal subjects.

• Law enforcement agencies should not collect or maintain information about the political, religious, or social

views, associations, or activities of any individual or any group, association, corporation, business, partnership,

or other organization unless there is a legitimate public safety purpose, such as the information directly relates

to criminal conduct or activity. In the case of criminal intelligence, such information should not be collected

or maintained unless there is reasonable suspicion to believe that the subject of the information is or may

be involved in criminal conduct or activity and the information is directly related to the criminal conduct or

activity.

• Law enforcement policy directives must dene:

» The circumstances under which conduct by personnel is authorized.

» The limitations on conduct by personnel.

• All law enforcement ocers and support personnel must be properly trained.

• If law enforcement action involves undercover activity, the following areas should be addressed:

» Supervisory approval.

» Required documentation of activity.

» Periodic reviews of activity.

» Audit of undercover processes and behavior, including authorization time frames for undercover

activities.

Regardless of the tools law enforcement personnel use to perform their duties, these principles help dene and place

limitations on actions undertaken by personnel and ensure the protection of individuals’ and groups’ privacy, civil rights,

and civil liberties. The implementation of these principles will help ensure that all law enforcement action is performed

with the highest respect for the law and for the community and will also help enhance the community’s trust in law

enforcement.

10 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Social Media

Policy Elements

Articulate that the use of social media resources will be

consistent with applicable laws, regulations, and other

agency policies.

Background: Social media should be viewed as another tool in the law enforcement toolbox and should be subject

to the same policies and guiding principles as other investigative methods and tools, including the identication of

reasonable suspicion, a criminal predicate, or a criminal nexus and adherence to the agency’s legal authorities and mission

requirements.

Action: As a part of the agency’s authorized law enforcement purpose, social media sites may be accessed to follow up on

tips and leads, suspicious activity reports, investigative support, development of criminal intelligence, and the development

of situational awareness reports. An agency policy on the use of social media resources as a part of investigative and

intelligence-related activities should be similar to agency policies regarding the use of other investigative tools, such as

undercover activities or accessing other types of open source information (e.g., Accurint or Internet-based search engines).

Further, the social media policy should specify that personnel should be able to articulate the purpose of using information

from social media sites, answering the questions “What are you using?” “Why are you using it?” “How did you use it?” and “Is

there a time frame on its relevance?”

As a part of this continuity, a social media policy should specically address:

• When the use of social media sites is authorized.

• The supervisory authorization process (if needed).

• Limitations on using information from social media sites.

• When and how social media sites may be accessed (e.g., during working hours or via agency resources).

1

Element

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 11

Define if and when the use of social media sites or tools

is authorized (as well as use of information on these sites

pursuant to the agency’s legal authorities and mission

requirements).

Background: Agency leadership and policymakers should be knowledgeable of applicable laws and regulations (including

the U.S. Constitution; the Bill of Rights, specically the Fourth Amendment; the state constitution; other laws; and 28 CFR

Part 23) when developing a social media policy and should know how these laws aect using information obtained from

social media sites.

Law enforcement has an obligation to comply with the Fourth Amendment. Every person has the right to be free from

“unreasonable searches and seizures” of their “persons, houses, papers, and eects.” These same protections may also

apply towards the use of social media sites—the uploading of pictures, the posting of activities, and the relationships

between and among individuals and groups. With the increasing use of technology and the free ow of information on the

Internet, it may be dicult to discern what access is reasonable and what would be deemed unreasonable under the Fourth

Amendment; therefore, a social media policy should clearly identify reasonable access to social media sites and the use of

information obtained from social media sites.

In addition to the Fourth Amendment, the Katz test

11

establishes a method that can also be utilized as agency personnel

analyze public or private information on social media sites. This test, based on Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967),

which addresses the expectation of privacy and intent to make information private, could also be applied to the use

of social media information, specically whether a social media site user has exhibited an expectation of privacy in the

information and whether the expectation is one that society is ready to recognize as reasonable. For information posted on

the Internet (via a social media site) that a user has made no eort to make private or conceal, applying the principles of the

Katz test would most likely result in a determination that the information is public. However, law enforcement personnel

should use that information only when there is an identied, valid law enforcement purpose.

28 CFR Part 23 may also assist agencies as they develop a social media policy. The 28 CFR Part 23 federal regulation has

become the de facto national standard regarding criminal intelligence information systems. Although 28 CFR Part 23

regulates systems, many of its tenets may be applicable to a policy regarding social media, such as storage, retention, and

sharing of information obtained from social media sites and resources. Additionally, 28 CFR Part 23 states that a project

“shall not collect or maintain criminal intelligence information about the political, religious, or social views, associations,

or activities of any individual or any group, association, corporation, business, partnership, or other organization unless

such information directly relates to criminal conduct or activity and there is reasonable suspicion that the subject of the

information is or may be involved in criminal conduct or activity.” This overarching purpose statement is also arguably

pertinent to information obtained by law enforcement personnel via social media sites, specically regarding what

information personnel can store, retain, and disseminate on political, religious, or social views, associations, or activities of

any individual or any group, association, corporation, business, partnership, or other organization.

Action: A social media policy should articulate the parameters regarding using information obtained from social media

sites. These parameters should be consistent with applicable laws, regulations, and other agency policies and further

articulate how privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties protections are upheld during such activities. It is important to note

that although information on many social media sites may be “open” (e.g., anyone with Internet access can view the

information), law enforcement must be mindful of what is legal, as well as what is consistent with community standards

and expectations, when using information from a social media site. In other words, simply because information is

11 See Appendix A for additional information on the Katz test and decision.

2

Element

12 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

available to law enforcement does not mean it should be used by law enforcement in the absence of a clearly dened and

valid law enforcement purpose. For example, a law enforcement investigator should search for and access an individual’s

Facebook prole when an authorized law enforcement purpose is identied, such as a search for a missing person or further

identication of an alleged criminal, and not to look for information on a new neighbor.

Relevant investigative laws, regulations, and policies should also be referenced in a social media policy. Articulating

laws, regulations, and policies, as they relate to the use of social media sites and information, will support the agency and

personnel in ensuring that they are using social media for a valid law enforcement purpose, adhering to established law

enforcement principles, and protecting citizens’ and groups’ privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties.

Additionally, a social media policy (or policy that addresses information obtained from social media sites) should address

the ever-changing nature of social media and associated technology. Technology advancements may aect the access and

collection of information from social media sites, and a policy should acknowledge that though technology may change,

the foundational elements for accessing social media sites remain consistent, such as accessing social media sites for an

authorized law enforcement purpose.

Articulate and define the authorization

levels needed to use information

from social media sites.

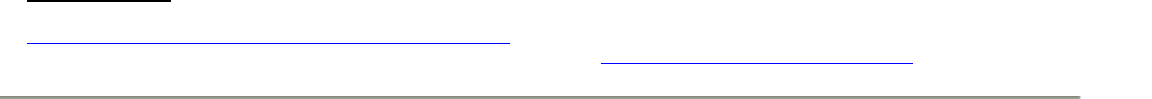

Background: Social media sites have varying and diering levels of access and engagement, ranging from “following”

someone on Twitter to “friending” someone on Facebook or simply searching for an individual or a topic via Google.

Engagement levels may also vary, from reviewing publicly available information on a social-networking site to accessing

social media resources from a

nongovernmental Internet Protocol

(IP) address to creating a user prole

or account for undercover operations

to lawful intercepts of electronic

information. Within the dierent

engagement levels are privacy, civil

rights, and civil liberties implications.

A social media policy should articulate

the levels of engagement by law

enforcement personnel with subjects

when accessing social media sites

and also specify the authorization

requirements associated with each level.

As part of the levels of engagement,

law enforcement personnel should

understand privacy settings, end-user licensing agreements, and terms-of-service requirements. Users may regulate their

privacy settings on their “prole,” which in turn could aect the level-of-engagement parameters. Additionally, companies

may articulate law enforcement engagement parameters via a terms-of-service agreement.

12

12 Many Internet- and communication-based companies have developed guides to assist law enforcement in understanding what

information is available and how that information may be obtained. Additional information on these guides is available at the IACP’s Center for

Social Media, at http://www.IACPsocialmedia.org/investigativeguides.

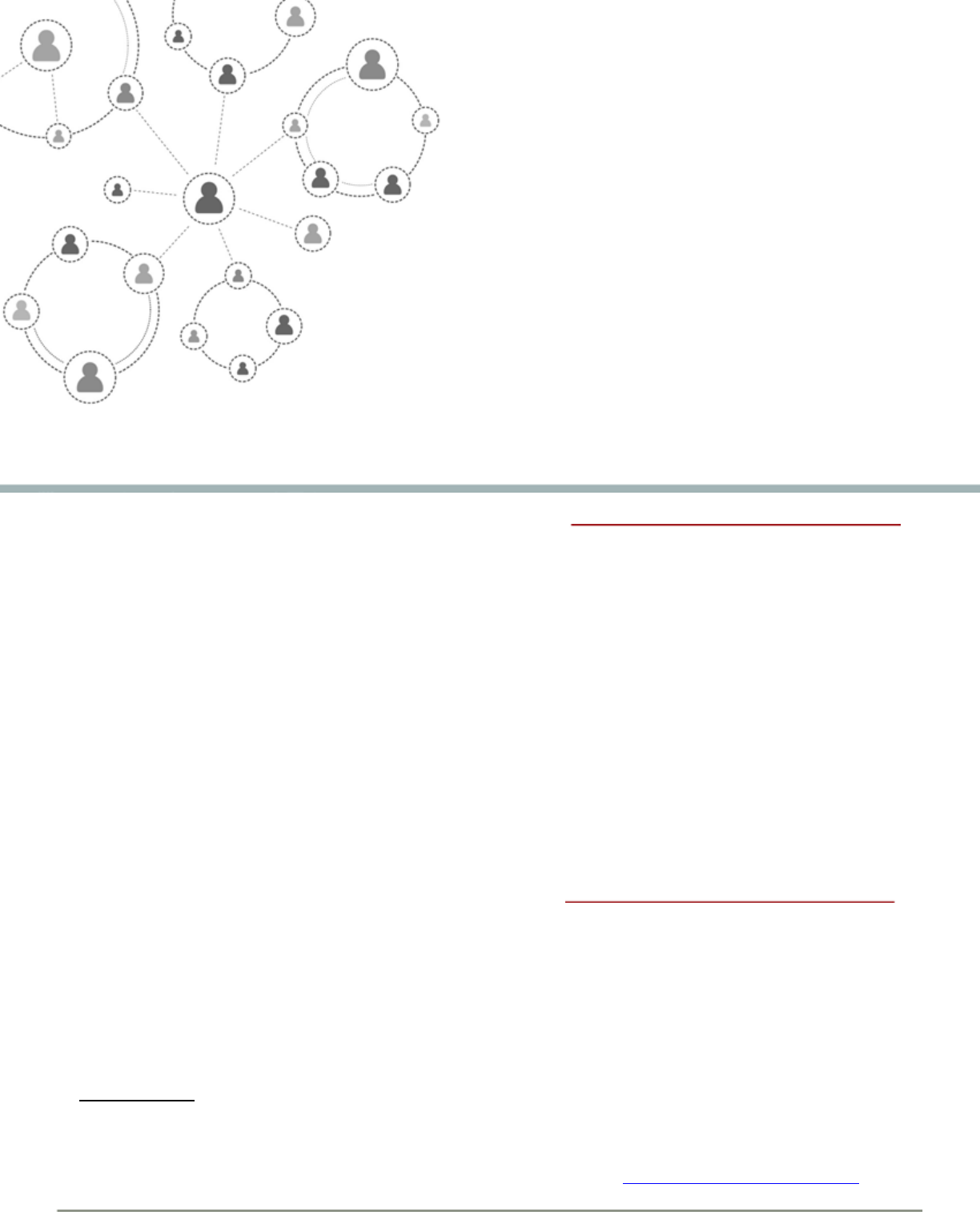

Tradional

Law Enforcement

Acons

Social Media

Acons

Uniformed

Patrol

on the Street

Plainclothes

Officers/

Detecves

Undercover

Officers/

Full Invesgaon

• “Googling” Someone

• Searching Facebook

• Searching YouTube

• Searching and Retaining

Public Access Pictures

• Retaining Profile Status

Updates

• “Friending”

• “Following”

• Seng Up User

Account

• Lawful Intercepts

Apparent/Overt Discrete Covert

3

Element

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 13

To assist in understanding how information from social media sites can be used by law enforcement, the graphic above

provides a visual demonstration of the comparison between traditional law enforcement practices and specic social media

actions. As identied in the graphic, examples of levels of engagement include:

Apparent/Overt Use—In the Apparent/Overt Use engagement level, law enforcement’s identication need not be

concealed. Within this engagement level, there is no interaction between law enforcement personnel and the subject/

group. This level of access is similar to an ocer on patrol. Information accessed via this level is open to the public (anyone

with Internet access can “see” the information). Law enforcement’s use and response should be similar to how it uses and

responds to information gathered during routine patrol. An example of Apparent/Overt Use would be agency personnel

searching Twitter for any indication of a criminal-related ash mob to develop a situational awareness report for the

jurisdiction.

Apparent/Overt Use is based on user proles/user pages being “open”—in other words, anyone with Internet capabilities

can access and view the user’s information. For instance, if an ocer searches for a criminal subject’s Facebook page and

determines that a prole which appears to be that of the subject has the account privacy settings set to “public” (meaning

the information can be viewed by everyone), then the use of that information would be considered Apparent/Overt Use.

The authorization level for Apparent/Overt Use may be minimal, as this level of engagement is considered part of normal,

authorized law enforcement activity (based on the law enforcement purpose).

Discrete Use—During the Discrete Use engagement level, law enforcement’s identity is not overtly apparent. There is no

direct interaction with subjects or groups; rather, activity at this level is focused on information and criminal intelligence

gathering. The activities undertaken during the Discrete Use phase can be compared to the activities and purpose of an

unmarked patrol car or a plainclothes police ocer. An example of Discrete Use is an analyst utilizing a nongovernmental

IP address to read a Weblog (or blog)

13

written by a known violent extremist who regularly makes threats against the

government. Bloggers (those who write or oversee the writing of blogs) may use an analytical tool to track both “hits” to

the blog and IP addresses of computers that access the blog, which could potentially identify law enforcement personnel

to the blogger. This identication could negatively impact the use of the information and the safety of law enforcement

personnel, who would not want to reveal that they are accessing the blog for authorized law enforcement purposes. In

many cases, direct supervisory approval may not be necessary within this level of engagement, but the policy should

address agency protocol.

Covert Use—During the Covert Use engagement level, law enforcement’s identity is explicitly concealed. Law enforcement

is engaging in authorized undercover activities for an articulated investigative purpose, and the concealment of the ocer’s

identity is essential. An example of Covert Use is the creation of an undercover prole to directly interact with an identied

criminal subject online. Another example is an agency lawfully intercepting infomation from a social media site, through

a court order, as a part of authorized law enforcement action. Clear procedures should be identied and documented on

the use of social media in this phase, since there are many privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties implications associated

with Covert Use. Agencies should also review social media sites’ information for law enforcement authorities and terms of

service for additional information on undercover proles.

Authorization levels for Covert Use activities should be clearly identied and could be compared to authorization levels

needed for any undercover investigative activity (such as undercover narcotics investigations).

Action: An agency’s social media policy should identify the agency’s dened levels of engagement that will be utilized

by agency personnel, the types of activity associated with these levels, and direct authorization requirements, if any,

13 For additional information on blogs, please visit http://www.IACPsocialmedia.org/blogfactsheet.

14 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

associated with each level from use as a part of ocial law enforcement activities (e.g., the checking of social media sites is

built into the analytic product development process) or direct supervisor approval requirements (such as development of an

undercover prole to interact with a criminal subject). For example, if an agency uses social media to gather or disseminate

information regarding a First Amendment-related event that has become violent in other jurisdictions, it is essential to

clearly dene any limits on the collection and use of information from social media.

14

Specify that information obtained from social media

resources will undergo evaluation to determine confidence

levels (source reliability and content validity).

Background: The evaluation of information—be it for criminal intelligence purposes or for criminal investigative

purposes—may have dierences. With regard to criminal intelligence, information should be assessed to determine

its validity and reliability, and products produced as a result of this information should include proper caveats. In some

instances, it may be dicult to determine the validity of information obtained from a social media site (e.g., a citizen submits

a tip about a video posted on YouTube depicting a robbery); however, that information may still be considered a potentially

valid tip and should be documented as such.

In the case of a criminal investigation, information obtained from a social media site should be further evaluated to

ensure that the information is authentic. For example, a video posted on YouTube shows individuals allegedly robbing

a convenience store; law enforcement personnel should obtain a subpoena to determine what IP address was used to

upload the video and identify to whom the IP address is registered. Information obtained from social media sites can be a

valuable tool; however, comprehensive evaluation and authentication are crucial to ensure the reliability and validity of the

information and ensure proper caveats are included, as necessary.

Case law has recently been established regarding authentication of information obtained by law enforcement. In Grin

v. Maryland, 2011 Md. LEXIS 226 (Md. 2011), the appeals court ruled that MySpace pages were erroneously admitted into

evidence because they had not been properly authenticated. The trial court admitted the postings based on a police

ocer’s testimony that the picture in the prole was of the purported owner and that they had the same location and date

of birth. The picture, location, and birth date did not constitute sucient “distinctive characteristics” to properly authenticate

the MySpace printouts of the prole and posting because of the possibility that someone else could have made the prole

or had access to it to make the posting. The court stated that there are dierent concerns when authenticating printouts

from social media sites that go beyond the authentication concerns of e-mails, Internet chats, and text messages. Some

suggested approaches to the social media authentication issue include an admission by the purported prole owner that

it is his or her prole and he or she made the postings in question, a search of the person’s computer and Internet history

that links the subject to the prole or post, or information obtained directly from the social media site that identies the

person as the prole’s owner and the individual with control over it, possibly including IP address identication information.

This case demonstrates the need to validate information obtained from social media sites. As a source of information for

lead development and follow-up, social media can be a valuable tool, but law enforcement personnel should always

authenticate and validate any information captured from a social media Web site.

Action: A social media policy should articulate that any information obtained from social media sites be evaluated to

determine accuracy, validity, and/or authenticity. Social media interaction and usage are based on user uploads and updates

and therefore should not serve as a primary/sole source for information gathering and verication. As with all sources

of information, independent validation is important to determine accuracy and, more important, to protect individuals

14 See Recommendations for First Amendment-Protected Events for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies for additional information on

law enforcement’s role regarding First Amendment-protected events.

4

Element

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 15

from being incorrectly identied, possibly leading to privacy violations and/or other inappropriate actions. Agencies

may also refer to other policies and procedures related to criminal intelligence and investigative activities (and sources of

information) as a part of the evaluation and authentication processes of information obtained from social media sites.

Specify the documentation, storage, and retention

requirements related to information obtained from social

media resources.

Background: Based on the purpose for gathering information via social media resources (e.g., intelligence development,

analysis assessment, or criminal investigations), agencies should identify the storage and retention requirements (why and

for how long this type of information should be retained).

15

For criminal intelligence development and products, agencies

may reference the storage and retention requirements identied in 28 CFR Part 23. For the documentation, storage, and

retention requirements of information obtained from social media sites that is being utilized for a criminal investigation,

agencies should refer to their investigative policies and procedures (and applicable laws and regulations).

If personally identiable information (PII) (such as a name, a date of birth, or a picture) is identied and collected from social

media sites, agencies should be sensitive to the documentation and retention of this information. If the information is part

of criminal intelligence development, it is recommended that the tenets of 28 CFR Part 23 be followed; if the information

is part of a criminal investigation, it is recommended that agency policy and procedures related to the dissemination of

investigative information be referenced.

The documentation of this type of information should specify the purpose of the information use (regardless of the source

of information), what information was collected (photos, status updates, friends), when the information was accessed and/

or collected, where the information was accessed (identify the Web site), and how the information was collected (open

search, nongovernmental IP address, undercover identity, etc.). Copies of the information obtained from the sites should

also be documented. Additionally, as law enforcement personnel access social media sites, the reason for the use of the

information obtained and the site utilized should be specied in the case or intelligence le.

For analysis assessments, the storage and retention period will be contingent on the assessment ndings and whether

a valid law enforcement purpose was identied. For example, a local law enforcement agency sends a request for

information to the state fusion center to determine whether there are any threats or potential criminal activity associated

with an upcoming demonstration. The fusion center creates an awareness assessment and references information obtained

from social media resources that articulates that there are no threats identied. Further, the demonstration was peaceful,

with no arrests. No potential criminal predicate or criminal nexus was identied either in the assessment itself or during

the event, and therefore there is no articulable reason to store the information that was obtained as part of the analysis

assessment.

For intelligence development purposes, the requirements of 28 CFR Part 23 should be followed regarding storage and

retention of all information, whether collected from social media sites or other information sources. Though not all

intelligence systems are required to adhere to 28 CFR Part 23, it has become a de facto national standard,

16

and as such,

agencies are strongly encouraged to incorporate the tenets of this regulation into their policies and procedures regarding

all criminal intelligence-related information.

15 For additional information on le guidelines for criminal intelligence, please refer to the LEIU Criminal Intelligence File Guidelines,

http://it.ojp.gov/documents/ncisp/criminal_intel_le_guidelines.pdf.

16 See the National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan, Recommendation 9, http://it.ojp.gov/documents/NCISP_Plan.pdf.

5

Element

16 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

If information from a social media site was gathered as part of a criminal investigation—such as a photo, identication

of associates, or other PII—law enforcement personnel should adhere to agency policies and procedures regarding the

documentation and storage of such information, carefully noting when and where the information was gathered.

17

A

policy should also address the need to print or record the information gathered from the site to include in the case le for

evidentiary purposes, due to the ease of changing social media information (users deleting information, changing their

settings, etc.).

Action: The documentation, storage, and retention requirements for information obtained from social media resources

should be articulated and dened in a social media policy. This section of the policy should be comparable to other

investigative and/or intelligence policies regarding information documentation, storage, and retention.

Identify the reasons and purpose, if any, for off-duty

personnel to use social media information in connection

with their law enforcement responsibilities, as well as

how and when personal equipment may be utilized for an

authorized law enforcement purpose.

Background: The ease and accessibility of social media resources (including the use of applications [or apps] for

smartphones and tablet computers) may aect how law enforcement personnel access social media when o duty,

18

as well

as the use of personal equipment and personal accounts for ocial agency purposes. The information that is collected may

result in criminal intelligence or lead to an active investigation; therefore, it is important to include a provision in the social

media policy to address using information from social media sites for a law enforcement purpose by o-duty personnel

and using nonagency equipment for ocial law enforcement purposes. With greater access to information through

social media sites, it may be easier to identify criminal subjects and/or criminal activity, but it is also imperative to identify

approved uses and access to the information.

For example, a law enforcement ocer is o duty and is posting an update on his Twitter page. As part of his accessing

Twitter on his personal computer, he notices a trending topic for his city about a robbery at a jewelry store. The agency’s

social media policy might require that the ocer report this issue to dispatch and conduct a follow-up eld incident report,

documenting what he viewed, the site where he viewed the information, when he viewed it, and any action based on

the information. In another example, an analyst is viewing her friends’ status updates on Google+ and notices one friend

expressing outrage at recent government policies (the friend does not make any threats, just articulates dissatisfaction).

This posting is part of her friend’s First Amendment right to free speech, and therefore no law enforcement documentation

or other action should take place.

In another example, an intelligence ocer who is focused on gang-related crime uses his personal Twitter account to

“follow” a subject-matter expert (SME) in the eld of gang identication and trends, as authorized in the agency’s policy,

which includes the provision for law enforcement ocers to access social media sites, via personal accounts, as a part of

their authorized law enforcement mission. The ocer regularly updates his supervisor and intelligence unit members of

trends identied by the SME and how these trends may be carried out in the jurisdiction.

Because of the widespread use of social media, agency policy must articulate when and how it is acceptable for o-duty

personnel to use information from social media sites as part of their law enforcement mission. Law enforcement personnel

17 It is important to note that the gathering of information from a social media site may be the result of a court-ordered lawful intercept.

As such, there may be specic instructions regarding the gathering and storage of information.

18 The IACP’s Center for Social Media identies ve key policy considerations for agency policies regarding the use of social media,

including the use of social media for personal use. See http://www.iacpsocialmedia.org/GettingStarted/PolicyDevelopment.aspx.

6

Element

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 17

must adhere to law enforcement principles, whether on duty or at home surng the Internet for a law enforcement

purpose.

Action: A policy that addresses social media information should specify whether or not o-duty personnel may, as a part

of an authorized law enforcement purpose, access social media sites and the reason(s) (if any) and requirements for access.

If authorized, the policy should address the parameters in regards to accessing information that is viewed and gathered by

o-duty personnel (for an authorized purpose), restrictions on the use of work equipment and/or personal equipment in

an ocial law enforcement capacity while o-duty, and how to document and report the information that is gathered from

the social media site.

19

The policy should also specify whether or not law enforcement personnel may, when carrying out their authorized law

enforcement mission and function, use personal equipment (including personal accounts) to access information via social

media sites and the reason(s) and requirements associated with the use of personal equipment for this purpose. If the

policy indicates that it is acceptable to use personal equipment for ocial agency purposes, then the policy should also

direct personnel to document how information was obtained, the type of information obtained, the reason the information

was obtained, and any follow-up action.

Identify dissemination procedures for criminal intelligence

and investigative products that contain information

obtained from social media sites, including appropriate

limitations on the dissemination of personally identifiable

information.

Background: Because of the open nature of many types of information obtained from social media sites, it is important to

articulate dissemination procedures of products, reports, and requests for information that include information from social

media sites.

20

Additionally, the use of social media sites that focus on advocating greater information sharing among law enforcement

agencies and personnel should be addressed in a policy. These sites oer greater access and information sharing

capabilities; however, sharing any type of law enforcement information should be limited to nationally recognized sensitive

but unclassied (SBU) networks (e.g., Regional Information Sharing Systems® [RISS], Law Enforcement Online [LEO],

Homeland Security Information Network [HSIN]) and not social media/open source, commercially developed platforms.

Action: A social media policy should address dissemination protocols (who to disseminate to, timeline restrictions, how

to disseminate information) for law enforcement reports, products, bulletins, and other types of information that may

include information obtained from social media sites (and contain criminal intelligence information, criminal investigative

information, and other information containing PII). Additionally, because of the sensitive nature of this type of information,

the policy should address the incorporation of a review from a privacy ocer and/or general counsel when disseminating

products that include information from a social media site (including biographical information, photos, locations of

subjects, etc.). A policy should also address dissemination mechanisms, such as using secure e-mail and SBU systems (not

open source systems) to share criminal intelligence versus the use of social media sites to post bulletins to educate the

public about criminal activity in the community.

19 The IACP’s Center for Social Media further addresses employee personal use of social media.

20 For example, the validity and reliability of PII (e.g., photos, videos, and biographical information on a subject) that was obtained from

social media sites may be unknown.

7

Element

18 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Conclusion

Social media sites and resources may be a helpful tool for law

enforcement personnel in the prevention, identication, investigation,

and prosecution of crimes. Though social media sites are a relatively

new resource for law enforcement, the same principles that govern all

law enforcement activities should be adhered to as personnel access,

view, collect, use, store, retain, and disseminate information from

these types of sites; the same procedures and prohibitions that are

placed on law enforcement ocers when patrolling the community or

conducting an investigation should be in place when law enforcement

personnel utilize social media as a part of their public safety function.

As with other law enforcement tools—such as uniform patrol,

undercover activities, and search warrants—it is important to have a

policy that articulates the how, when, and why of accessing, viewing,

collecting, using, storing, and disseminating information obtained

from social media sites, highlighting the privacy, civil rights, and civil

liberties protections that are in place, regardless of the information source.

Though social media sites are a relatively

new resource for law enforcement, the

same principles that govern all law

enforcement activities should be adhered

to as personnel access, view, collect, use,

store, retain, and disseminate information

from these types of sites.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 19

20 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Appendix A—Cases and Authorities

These cases and authorities were relied on in the construction

of the Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in

Intelligence and Investigative Activities: Guidance and

Recommendations document. While these may be persuasive,

it is always prudent to have agency legal counsel examine

them in light of the controlling legal authorities in your

jurisdiction.

Fourth Amendment Privacy Law and

the Internet

Expectation of Privacy in Internet Communications,

92 A.L.R.5th 15, contains a good summary of current law

regarding many forms of Internet communication, including

e-mail messages and inboxes, chat rooms, Web site content, and social-networking sites. Many cases cited within are

summarized below.

Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979), forms the basis of the “third-party exposure” doctrine of electronic privacy law. In

Smith, the government used pen register technology to record the numbers dialed out from a certain phone number. This

information was used to convict the defendant of robbery. The defendant challenged the use of the pen register as an

illegal search under the Fourth Amendment. The court ruled that the defendant did not have a reasonable expectation of

privacy in the phone record information because the information was automatically turned over to a third party, the phone

company. Even if the defendant had an expectation of privacy in the numbers dialed, it was not one society recognized as

reasonable—therefore, there was no Fourth Amendment violation. This case has been analogized to Internet subscriber

information, such as account existence and information on who the registered user of the account is because this

information is automatically exposed to a third party, the Internet service provider.

Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities 21

United States v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945 (2012), is a case involving law enforcement’s placement of a Global Positioning System

(GPS) device on a subject’s car and use of the device to monitor the vehicle’s movement on public streets for a four-week

period (which extended beyond the period of time and place authorized by a search warrant). The Supreme Court Justices

unanimously agreed that use of the GPS device constituted a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

The majority explained that a physical intrusion into a constitutionally protected area, coupled with an attempt to

obtain information, can constitute a violation of the Fourth Amendment based upon a theory of common law trespass.

The majority explained that “the use of longer-term GPS monitoring in investigations of most oenses impinges on

expectations of privacy.” Additionally, in a separate opinion, one justice suggested that it may be time to rethink all police

use of tracking technology, not just long-term GPS, reasoning that “GPS monitoring generates a precise, comprehensive

record of a person’s public movement that reects a wealth of detail about her familial, political, religious, and sexual

associations…. The government can store such records and eciently mine them for years to come.” The reasoning

expressed by the justices in Jones could have broad implications for law enforcement use of social media in such areas as

law enforcement personnel access to information from social media sites and the determination as to whether the social

media user has a reasonable expectation of privacy due to privacy controls set up by the user.

United States v. Kennedy, 81 F. Supp. 2d 1103 (D. Kan. 2000). Relying on Smith (above), the District Court of Kansas ruled

that the defendant did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in information knowingly turned over to his Internet

service provider, including Internet subscriber information and information associated with his Internet Protocol (IP)

address. Divulgence of this information to law enforcement by Road Runner cable did not violate defendant’s Fourth

Amendment rights. See also United States v. Ohnesorge, 60 M.J. 946 (N.M. Ct. Crim. App. 2005) (the court did not abuse

its discretion in refusing to suppress Internet service provider information, specically subscription information to a news

and le access sharing Web site obtained without a warrant. The defendant did not have a reasonable expectation of

privacy in the information; the subscription information was never condential, and the defendant acknowledged that the

information could be shared in the terms of service agreement with the site).

Social Media and Privacy Law

Nathan Petrashek Comment, “The Fourth Amendment and the Brave New World of Online Social Networking,” 93 Marq.

L. Rev. 1495 (summer 2010). This law review article provides a thorough background on social-networking sites and how

the two largest, MySpace and Facebook, operate. A current case law summary is provided as well as an explanation of

dierent privacy doctrines and how they can be applied to the social media setting.

Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967), provides the foundation for most federal court privacy rulings and doctrines.

Katz moved away from previous Supreme Court privacy jurisprudence in holding that the Fourth Amendment protects

people and not places, overruling the previous “trespass” doctrine of Fourth Amendment protection. Fourth Amendment

considerations no longer require a physical invasion or trespass. In this case, police eavesdropped on private conversations

from a public telephone booth, and the court found that even though no physical invasion of the phone booth occurred,

this was not necessary to constitute a search for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. Police violated the defendant’s

Fourth Amendment privacy interests by listening to the content of the conversations without a proper warrant. Katz

established a two-prong test to determine whether the Fourth Amendment is implicated and a search has occurred. If

a person, like Katz, has manifested an intent to make the information private and society accepts that expectation of

privacy as reasonable, then that privacy expectation cannot be violated without following Fourth Amendment warrant

requirements.

22 Developing a Policy on the Use of Social Media in Intelligence and Investigative Activities

Minnesota v. Olson, 495 U.S. 91 (1990), further explained the application of Katz and the two-prong expectation of privacy

test. As an overnight guest, the defendant did have an expectation of privacy in the dwelling, and that expectation is

recognized by society as reasonable.

Courtright v. Madigan, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 102544 (S.D. Ill. 2009). The defendant was convicted of three separate

oenses of producing, possessing, and receipt of child pornography by a repeat oender. The case initiated through a

subpoena served on MySpace.com by the Illinois Attorney General’s Oce in an eort to learn whether any registered sex

oenders were using that site. Upon learning the defendant had a MySpace account, investigators took further steps to

discover his IP address and learned that this address had oered pornographic images on the le-sharing site Limewire.

These discoveries formed the basis of a warrant that uncovered evidence that was used to convict the defendant. The

defendant argued that the initial information gathered from MySpace regarding his account violated his protection against

unreasonable searches and seizures under the Fourth Amendment. For other procedural reasons, the defendant’s appeal

was denied, but the court addressed the search issue and, relying on multiple other courts, held that the defendant had no

privacy expectation in Internet subscriber information based on the third-party exposure doctrine. The defendant had no

expectation of privacy in the fact that his MySpace account existed, so the request for information on that matter did not

violate his Fourth Amendment rights.

Commonwealth v. Proetto, 771 A.2d 823 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2001). In Proetto, the defendant was brought to the attention

of police after a 15-year-old female who had been contacted by the defendant in a public chat room turned over logs of

chats that contained explicit information and solicited sexual activity from the underage girl. Police asked the informant

to cease communication with the defendant but inform them when he was online again. When police were informed that

the defendant was online, they entered the chat room the defendant was in, posing as a 15-year-old girl. The defendant

made sexually suggestive comments to the “underage female,” which law enforcement ocers logged. The defendant

challenged use of the chat room logs and e-mail messages under the Fourth Amendment and Pennsylvania Wiretap Act.

First, for the communication forwarded to police from the underage informant, the court analogized the e-mail and chat

communications to letters and found a limited privacy right. As with letters, the expectation of privacy in the information

was reasonable until the intended recipient received the information. After that, because the information could easily

be forwarded to others, there remains no reasonable expectation of privacy; therefore, there was no Fourth Amendment

violation. For the chats, the defendant did not know exactly whom he was speaking to so he did not have a reasonable

expectation of privacy. Communications made directly to the undercover ocer survive Fourth Amendment challenges

under the same reasoning in that the defendant has only limited privacy interests in e-mail communications. Because the

defendant communicated freely with the undercover ocer and could not verify the ocer’s identity, he had no reasonable

expectation of privacy in the chat communications. The fact that the ocer did not identify himself as law enforcement is

of no consequence. The Pennsylvania Wiretap Act was not violated because the informant and the police were both the

intended recipients and parties to the communication and recorded the messages concurrently with the communication.

For similar case law, see United States v. Maxwell, 45 M.J. 406 (C.A.A.F. 1996) (no expectation of privacy found in e-mail

communications in child pornography case); United States v. Charbonneau, 979 F. Supp. 1177 (S.D. Ohio 1997) (explaining

chat room and privacy expectations around Internet service providers, nding no reasonable expectation of privacy); and

Ohio v. Turner, 156 Ohio App. 3d 177 (Ohio Ct. App. 2004) (no expectation of privacy in chat room conversations with

undercover agent posing as underage boy).

Guest v. Leis, 255 F.3d 325 (6th Cir. 2001). After receiving a tip regarding online obscenity, police began investigating two

electronic bulletin board systems. Police assumed an undercover identity to receive a password to the bulletin board,